Tshaka Cunningham, Ph.D.: So if you could all grab your Bibles and stand. It says, “I will praise thee for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” Thanks be to God for the reading of His words.

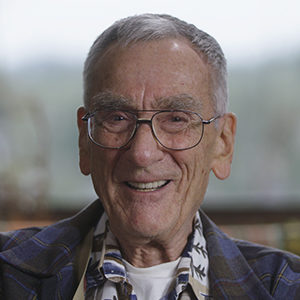

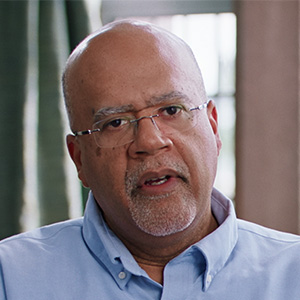

Part of being a molecular biologist is like a philosopher of sorts of this is you get you get to really think about inner space. The magnitude of information that’s encoded in DNA. It’s amazing. And to me it’s really spiritual. The science that I do I’m a bit of a unicorn in that sense, but a scientist that believes in God, right?

I was kind of born into it as a kid. My mother was an artist and we didn’t have a lot of money. My peers could go to summer camp. We couldn’t afford that for me, but my grandmother had a stable job as a biologist at the NIH. So my grandmother would take me to lab with her. She did research on small cell lung cancer at the National Cancer Institute for many many years. And she’s one of the first African Americans there.

I remember my grandmother would take a piece of parafilm and would dot water with food coloring and make me practice my pipetting. So I would spend hours doing that. Oh yeah. By the time I was like nine years old, I probably had the pipetting skills of like you know a 20 year lab veteran. Cause I’d been doing it for a long time.

I see the tremendous disconnect between genomic technology and the communities. If you look at the standard publicly available, let’s say cancer genomic database, very heavily homogeneously Caucasian. Probably in the 90 percents or more. Whereas the US population is not that way.

Interviewer: If a particular group of people isn’t represented what’s the consequence?

Cunningham: Then that particular group of people, presumably, is not gonna benefit as much. My goal is to get as many, particularly people of color minorities, genome sequenced as possible.

Every time I’m in the house of the Lord I love to read scripture. So if you all would indulge me I’d like to share two scriptures with you that that helped me set the framework for what some of the knowledge I’m gonna share. Hosea, The Book of Hosea, the fourth chapter and the sixth verse: “My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge.” I’m gonna share with you today some information about how God made us. We’re fearfully and wonderfully made.

As medicine gets much more precise and based on an individual’s genetics we’re all gonna have to get a lot more genomically literate. The knowledge that I’m gonna share with you today is knowledge that we as a people, particularly African Americans, cannot afford to lack. It’s the knowledge of who we are, where we came from, and what our health future is.

I view science very much as a conversation with nature. And that is a very special, and for me, a very spiritual thing. Nature is something in my belief God created. Psalm 139: “For I am fearfully and wonderfully made. Marvelous are thy works.”

There’s so much that we don’t understand. You know, it’s the essence of things, hope for the evidence of things not seen. Faith. One of my conceptualizations of heaven is when we get there, we’ll get all of the all the answers to all the questions that that we wouldn’t have been able to answer as humans.

My grandmother recently passed away at the age of 83 from triple negative breast cancer. As she, you know, got her diagnosis, I was really asking her to get sequenced so that her nieces would sort of be able to ascertain a bit their risk. And she was very apprehensive to do it, “I don’t want folks, these folks having my DNA.”

It was hard cuz it was frustrating cuz I was like, “Grandma, you know.” I was like, “You’re a scientist. You know, you’ve done cancer research.” Having your genome sequence was this new technology that even she didn’t really understand that well yet, but she wound up doing it.

You have to understand my grandmother was a black woman first. You know she knew of folks who actually afflicted by the Tuskegee city. They were in her generation; she was born in 1933. Even with her dedication to research, still a very robust distrust of the medical establishment. That’s where you know folks like me could have a lot of impact. As we get more information about everybody’s DNA, your medical treatment is gonna get a lot more specific a lot more precise.

A woman that was there, she might have been in her eighties and she reminded me of my great aunt, and she came up and grabbed my hand and said, “Baby I love the way you described that.” And that really just I mean it really you know. I felt really good in that moment. I’m breaking through, you know, if I can get you know 80 year old church-going black women to understand this, I’m gonna get the whole community to understand it. And we’ll be on better footing as a patient population.

So this is a saying I wanna leave you all with, “Love thy neighbor love thyself. I was thinking: Know thy genome know thyself. Help thy neighbor’s better health.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2010/02/henrietta-lacks-and-race/35286/

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overlooked-henrietta-lacks.html

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henriettalacks/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/index.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6137767/

https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html

Executive Producers: Elliot Kirschner, Sarah Goodwin, Shannon Behrman

Producers: Regina Sobel, Brittany Anderton, Meredith DeSalazar

Cinematographers: Derek Reich, Alexis Keenan, Jimmy Purtill, Ryan Maslyn, Josh Weinhaus, Amanda McGrady

Editor: Elizabeth Brooke

Interviews: Adam Bolt

Graphics: Chris George, Maggie Hubbard

Music: Marcus Bagala

Sound: Jonathan Cohen